Designing neighbourhood health centres that last: sustainability through the lenses of 4 theories and frameworks

My last blog on team management in neighbourhood health centres sparked energetic debate on LinkedIn and beyond - and rightly so. Direct messages from people have been appreciative of the inclusion of some theoretical perspectives and evidence from the management literature - especially from the view point of a dual qualified doctor and Chartered Manager blending theory with the reality of working at the coal face. Thanks all for your engagement!

Beyond team management, there is a much wider debate about whether neighbourhood centres will really make a difference, and whether they will last into the future.

The 10 Year Health Plan firmly places neighbourhood health centres (NHCs) as a core feature of the local health and care landscape and as a means to address the wicked problem of health inequalities, so they are going to have to be sustainable. Sustainability is a wicked problem in its own right - complex, multi-layered and without simple solutions. It also more than the green agenda: it's about creating something that adapts, learns and persists through the complexity of the modern world.

In this blog, we'll explore:

- Wicked problems

- Systems thinking

- Symbiosis in Development

- Autonomy and accountability for public service organisations

- Asset based community development

Defining Wicked Problems

The term wicked problem was coined in the 70's by Rittel and Webber and describes challenges that:

- Have no definitive formulation

- Don't have a "stopping rule" - you can't declare them permanently solved

- Are symptoms of other problems within a wider interconnected system

- Don't have right or wrong solutions, just solutions that are better or worse

Health inequalities are wicked because they are influenced by multiple interdependent factor like healthcare, education, employment, wealth, the lived environment, transport and ethnicity - and these are all shaped by political, economic and cultural forces. (NB: the link is to the Marmot 10 years on report and is essential reading!)

As part of the solution, NHCs themselves will be operating within complex adaptive systems. so understanding systems thinking is useful in setting the design principles.

Defining the Sustainability Agenda

Sustainability is often confused with environmental stewardship, but it is a multidimensional concept which has historically been ill-defined. Some attempts to address this are becoming increasingly mainstream in organisational design and behaviour. For example, the triple bottom line: people, planet and profit; or Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR).

Sustainability encompasses many concerns:

- Ecological – protecting natural systems and biodiversity

- Social – fostering trust, inclusion, equity, and cohesion (World Health Organization)

- Economic – ensuring financial viability over the long term (Elkington, 1997 – Triple Bottom Line)

- Cultural – valuing local norms, stories, and identities (The Economics of Social Policy, Throsby, 2010)

- Wellbeing – promoting physical, mental, and community health (OECD Wellbeing Framework).

Personally, I like the definition provided by the SiD framework (which will discuss later in the blog) citing sustainability as a "state of a complex, dynamic system. In this state, a system can continue to flourish resiliently, in harmony, without requiring inputs from outside its system boundaries".

This definition and these dimensions point out that weakness in one domain (or from outside of a system) undermines all other dimensions. When thinking about NHCs sustainability means creating places that meet the human needs of their local communities now, without compromising the ability of future generations to do the same. It's a tall order, and the NHS will never hold all the cards or have all the answers.

A Systems Thinking Perspective

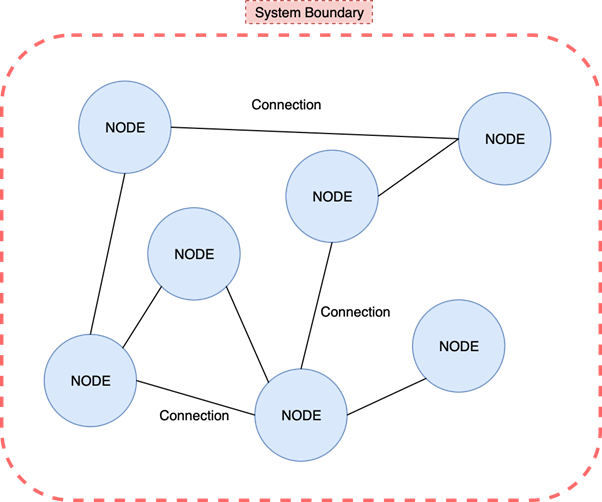

Systems thinking - a theory and practice which has evolved over many years and informed by influential thinkers like Jay Forrester, Stafford Beer, Geoffrey Vickers, Peter Checkland and Russell Ackoff, and more recently brought to our attention by Donella Meadows - would have us classify neighbourhood health centres as nodes, held together by connections within a wider defined network (the system boundary). In systems thinking language, nodes can be tangible objects, people, entities or abstract concepts. Connections represent the flow of energy, resource, information and influence between the nodes. Nodes can be related by single or multiple connects to one or more other node.

A neighbourhood health centre will connect multiple nodes - GP practices in the local PCNs, community services, specialised services in the community, social care, local authorities, voluntary groups, and residents - within a neighbourhood (a geographical boundary).

It is well worth mapping out a system and analysing the relationships to better understand patterns, feedback loops, consequences, and emergent behaviours that might be apparent from knowledge of a single partner/provider. You can't do this in isolation though - you're part of a system and each partner in your system will see parts that you don't, and have different knowledge and perspectives. Do it collaboratively!

From the systems thinking perspective, the design of NHCs must consider:

- Connections & Feedback Loops – a need ongoing information exchange and learning cycles, between nodes (or "system partners") which bolsters absorptive capacity (more on this in a future blog)

- Resilience – an ability to adapt to 'shocks' (think pandemics, sudden budget cuts, closure of a local GP practice...)

- Alignment of incentives that make sure all stakeholders benefit from the NHC’s success (remember people in your communities and patients are stakeholders too - and they should be the primary beneficiaries)

- Diversity & Redundancy – meaning that multiple actors and resources reduce the fragility of the system

Considering Symbiosis in Development (SiD)

I encountered SiD - a highly practical framework with a great repertoire of practical tools - by Tom Bosschaert at Except Integrated Sustainability during my own leadership training development. I found it very relevant and helpful in thinking about wicked problems and sustainability at both a node and connection level. In SiD, they are referred to as object and network level, respectively - with the system level as the big scale layer. This allows you to neatly 'zoom in and out' of a system.

Object level parameters

These objects (nodes) are all interconnected - but the nice thing about SiD is that they are in a structured in a nested hierarchy and should all be considered when thinking about sustainable systems. This hierarchy proposes that objects at the bottom of the list influence those above (think about Maslow's Hierarchy) We might call them wider determinants of wellbeing. It takes our thinking beyond people and organisations alone towards the full spectrum of physical objects in our world:

- Individuals - and their health and happiness

- Society - thinking about economy and culture

- Life - thinking about species and ecosystems

- Energy and materials

To what extent do you think from the offset about all of these layers when planning services?

Network level qualities

Consideration of the network level qualities is one of my favourite parts of the SiD framework. It consists of a number of indicators that help you analyse, reveal and understand the complexity of systems: which require autonomy, reliance and harmony to be resilient (the system level indicators in SiD. This really helps in analysing the connections posed by systems thinking in a detailed and structured way.

- Autonomy - the extent of self governance, self -sufficiency, circularity, efficient and mutual support

- Resilience - influenced by the structure, character and content of the system, including the culture and adaptability of the network

- Harmony - equity, inclusion and power dynamics within the network

Time, Space and Context

SiD encourages to make sense of how everything interrelated in a multidemsional way by thinking on different scales:

- Space - are you looking at something on a local scale in your neighbourhood, a 'place', regionally, nationally or even global?

- Time - what do the objects and their connections look like now? And how does that compare to the past and potential future?

- Context - the objects, networks and system and how they connect to other systems

Autonomy in SiD - the challenges for public services

For public service organisations (PSOs) - including the the NHS, local authorities and VCSE organisations - external funding, national policy, regulation and statutory duties all mean that organisations are accountable to somebody else and full autonomy is neither realistic nor desirable.

Accountability and autonomy frame the strategic context (Ongaro) for PSOs and is the equivalent to the external environment discussed in classical strategy books (which focus on competitive advantage that doesn't quite fit with public services).

At the moment there is opportunity for those developing NHCs: there is no national blue print to follow, which allows a degree of autonomy in design. There really needs to be situated agency - the local freedom to adapt and to innovate within a shared strategic, operational and regulatory framework. This balance can be achieved through innovating locally without breaching statutory regulation, building legitimacy with both local communities and the policy makers, and avoiding being dismantled by the policy churn within your own local systems/partnerships.

Asset-Based Community Development (ABCD)

While SiD and systems thinking frame sustainability structurally, Asset-Based Community Development, championed by Cormac Russell, brings it down to people and place. Building new NHCs cannot start from the point of statutory organisations trying to lead everyone else by the nose.

ABCD starts with the belief that communities are not simply passive recipients of services, but that they already hold skills, resources and relationships. Services should aim to connect and support these community assets, not displace or attempt to replace them.

For those developing NHCs this means, like systems thinking and SiD, you need to map out community strengths, assets and networks. The centres themselves should be designing space for connection, and not just service delivery.

Crucially, citizens within the neighbourhoods should be involved on an equal footing as co-designers and co-owners of solutions.

If you treat people as clients, they will become clients. If you treat them as citizens, they will act like citizens.”

Cormac Russel

Will Neighbourhood Health Centres Solve the Wicked Problem of Health Inequalities — and Be Sustainable?

The honest answer here is short: No.

Wicked problem theory and systems thinking tell us that no single model is going to solve health inequality. Wicked problems resist neat solutions. Every action that is taken reframes the problem, creates new issues and sparks fresh debate. That doesn't mean that NHCs cannot make a profound and lasting difference - but they need to be designed with deliberate care that considers the whole system, the whole community and with sustainability in mind. The risk of not doing so may well result in a new generation of Darzi centres - "expensive luxuries".

So how do these models and frameworks help us?

No framework or model will ever guarantee perfect solutions. Throughout my own leadership training and MBA I learned to recognise that models or theories should be never be used as a "how to guide" that can be applied to a situation, but as a different lens through which to look at challenges.

SiD helps us see sustainability not as a single target - but an interwoven set of conditions at object level (individuals, society, life, energy) and the network level characteristics that affect autonomy, resilience and harmony. Using this framework will help you design centres that are not just service hubs, but living parts of an interconnected system, that can adapt over many years into the future.

Systems thinking complements by helping us to consider how all the parts on a system interact - paying attention to feedback loops that help us learn and adapt; redundancy and diversity that foster the ability to keep going in adversity; and incentives that mean all partners are committed to doing the best by the community. It also reminds us that individual partners coming together to create neighbourhood health services are all nodes in a complex web. The effectiveness of each depends on the quality of connections with the others.

ABCD grounds us in the lived reality of local communities. It challenges us to start with the strengths within the community - citizen skills, passions and relationships. The centre needs to be a connector and catalyst for wellbeing, not a mere provider of services.

Together, and when used effectively these different concepts, models and theories can push us to create centres that are:

- Holistic - integrating social, cultural, economic and ecological concerns as strong contributors to health and wellbeing

- Connected - embedded in strong and adaptive networks

- Empowering - sharing power and enabling local citizens to co-create solutions

- Balanced - exercising local agency whilst remaining accountable to the 'system above'

What do you think? Can neighbourhood health centres — with the right design — be resilient enough to both reduce inequalities and thrive for decades to come?

I’d love to hear your perspectives, especially on how you see sustainability being built into real-world change.

Author | Dr Terry Hudsen

Dr Terry Hudsen is a UK-based General Practitioner with a portfolio career that spans clinical practice, system leadership and cross-sector collaboration.

In addition to his clinical work, Terry previously served as Chairman of NHS Sheffield Clinical Commissioning Group (CCG), leading strategic commissioning and system redesign, as well as leading the complex organisational change and transition to Integrated Care Boards. During this he led the establishment of joint commissioning arrangements between the NHS and local authorities and played a part in shaping national policy on maintaining joint health and care commissioning arrangements for local decision-making in place-based health and care systems.

Following the dissolution of CCGs in 2022, he became lead for Population Health and System Development in South Yorkshire’s Integrated Care System, before leaving the NHS to establish an independent consultancy supporting NHS providers, local authorities and VCSE organisations with their capabilities for developing collaborative leadership, strategy and tackling wicked problems.

In 2023, he became Independent Chair of the Bradford Safeguarding Adults Board, where he leads a statutory partnership which comprises partners from health, social care, local government, police, and the voluntary, community and social enterprise (VCSE) sector, focussing on preventing and responding to harm, neglect and exploitation of vulnerable adults.

Alongside these roles, Terry is Clinical Lead for Primary Care and Neighbourhood Engagement and Support within NHS England’s mental health portfolio in the North East and Yorkshire, helping to drive transformation and strengthen collaboration between providers of health and care at local level.

In addition to his medical qualifications from the University of Sheffield, Terry is a proud alumnus of The Open University Business School, where he earned an MBA with distinction in Leadership Practice. He is a Chartered Manager and a Fellow of the Chartered Management Institute. He is particularly interested in leadership across organisational boundaries, with his MBA dissertation focussing on collaboration between the NHS and VCSE sector.

In all his roles he emphasises the power of partnership, culture and shared learning in creating sustainable change. Passionate about building a culture of curiosity and shared purpose across public services, he writes and speaks about adaptive leadership, collaboration and innovation in complex systems. His work aims to inspire leaders and practitioners to think differently, work collectively, and create meaningful impact in the communities they work.

Article previously published on LinkedIn and Wicked Problems Hub.

December 2025

Would you like to contribute an article towards our Professional Knowledge Bank? Find out more.