What’s the problem we’re trying to solve in integrated care? Problem typology and frameworks

“What's the problem we’re trying to solve?” comes up all the time in meetings in public service partnerships.

Superficially, it seems like an easy question to define. In public services we don't have a shortage of issues... Access to see a GP, hospital waiting times, housing lists, health and social inequalities, and workforce pressures. Yet in practice, that seemingly simple problem question isn't actually easy to define!

Here's something to think about - problems aren't just things out there waiting to be picked up and solved. Problems are shaped by how we see them, describe them, measure them and even framed by the person who gets to describe them first in a meeting!

Spoiler: this article doesn't tell you what problems we are trying to (or need to) solve. It will outline some helpful frames to help you decide for yourself.

As with all my articles, I'll be looking at the management literature on problem definition through the eyes of a medical doctor and Chartered Manager, to help you engage critically with theories, models and frameworks for managing and leading.

Reality and representation

Problems are both real and represented. This is the same across all walks of life.

Let's work through this scenario:

NHS England reported nearly 360 million GP appointments in 2024 with one-in-five being delivered on the same day. GP appointments are at record levels.

However, how these facts are represented tells a different set of stories.

For some people, the representation tells a story of resilience in Primary Care in the face of system pressures, workforce shortages and funding squeezes.

For others, it might tell a story tell a story of waiting for a long time in pain for surgery, and the GP being your only point of care, but you still can't get an appointment!

For others still, it's a story of a crisis and the collapse of the NHS - with comparisons to the 'good old days' of seeing a GP whenever you wanted (did that ever exist?) and cries to 'bring back the family doctor'.

It all depends on the point of view.

Like a road and a map, both the reality of the terrain and the representation on paper (or your phone screen) matter.

There is a risk in any new neighbourhood health service development that we start acting on the representations without checking the reality. Or, that we cling to the harsh reality without noticing how it is being framed and lived by others. It isn't a case of one or the other, but both.

Different lenses to define problems

Problems as types

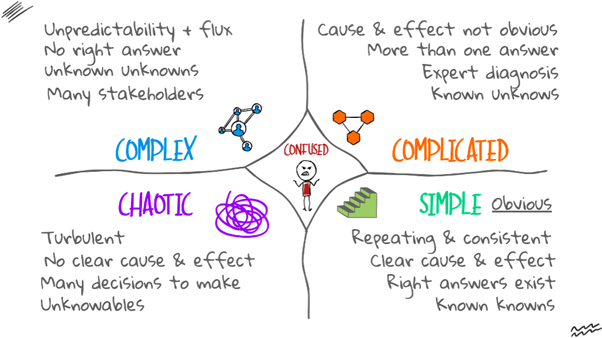

Not all problems are the same. The Cynefin Framework by Dave Snowden reminds of this. Some problems are simple (eg: scheduling appointments), others are complicated (eg: designing a new building), some are complex (health inequalities), and others are chaotic (eg: the sudden collapse of a service).

Knowing what type of problem you're dealing with is important in working out how to approach them. Get it wrong and there are risks! Think about neighbourhood health centres approaching health inequalities as a complicated problem, to be solved by experts, rather than a complex problem that needs co-produced solutions? I don't need to tell you that it probably won't make a difference...

The Cynefin Framework. Author's own diagram.

The framework suggests that:

- simple (obvious) problems need best practice

- complicated problems need good practice

- complex problems require collaborative emerging practice

- chaotic problems require novel practice

Cynefin helps us avoid reaching for the wrong tool! I've given a simplified account here, but I would recommend looking at the framework!

Problems as frames

Donald Schön and Martin Rein tell us that problems are not given, but they are framed.

In complex systems (such as NHCs) you'll see this theory showing up everywhere. Let's think about increased admissions for respiratory illness:

- A hospital clinician might frame the problem as workload

- A housing officer might frame it as unsafe conditions in cold homes with damp/mould

- Local residents frame it as not being listened to about local air pollution

All of these frames are valid, but they talk past each other.

This is where the concept of pluralism should be held in our minds... In an ideal world, there would be one agreed definition of the problem. In reality, multiple different perspectives will always exist.

Problems as political constructions

Murray Endelman puts forward the view that problems are not discovered, they are created.

In short, his theory argues that which issues get called "problems" depends on who has the microphone.

It's important to recognise these aren't lies (most of the time anyway), but they are political choices about which reality to represent and highlight to others. The role of leaders in NHCs then it to always ask: why is this problem being defined this way, and who does it benefit?

Wujec: frames, forces, structure... and using problem statements

Tom Wujec is famous for his TED Talk Got a wicked problem? First, tell me how you make toast. His approach is that many problems are too complex to hold in our heads, so we should draw them out. This links particularly well with systems thinking approaches, which I covered in a previous blog post.

When looking at problems, Wujec suggests we do similar when defining what the problem is, or developing a problem statement.

What I like about this approach is that it prompts us consider more than frames, structure or political constructs - it brings forces into the mix.

- the frames - who or what we are focussing on (eg: people, organisations, processes, transactions, objects). These are the nodes in system thinking

- the forces - the drivers acting are influencing the problem (eg: time, urgency, policies, legal frameworks, the energy required, resources, how many people need to be involved, power, control)

- the structure - the complexity and certainty within a problem (eg: our capacity to understanding or control the situation, and the number of interconnected parts and connections)

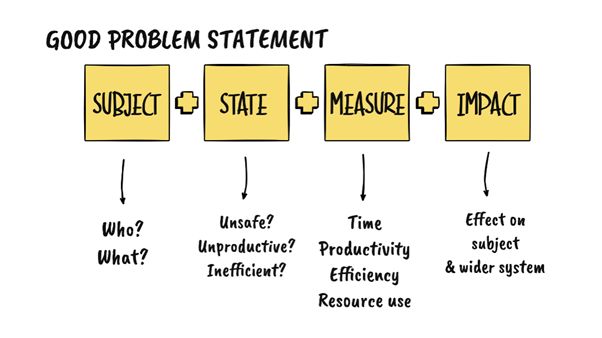

This problem then allows us to develop a problem statement, which contains:

- a subject (who/what) + a state (condition) + a measure (evidence) + the impact (why it matters)

A good problem statement: based on Wujec's work.

Here's a worked example

- Subject: older people who live alone

- State: at risk of social isolation

- Measure: 35% report loneliness in surveys

- Impact: increased rates of mental illness, cardiovascular disease, hospital admission, premature mortality

In developing a problem statement "loneliness" becomes less of a vague issue - it becomes more, defined, measurable, and linked with consequences.

From understanding to action

None of the theories mean much if they don't guide us to take action.

In medicine a diagnosis alone won't cure the patient, but it can help us reach for the best treatments.

- Cynefin helps us avoid treating complex, systemic issues as simple gaps

- Schön & Rein help us surface assumptions and negotiate frames rather than fight over solutions

- Edelman keeps us alert to politics, reminding us to check whose voice we are hearing

- Wujec prompts us to write sharper problem statements, based on thinking about whole systems

Final thoughts

Asking the question "what problem(s) are we trying to solve?" isn't just the warm up to the real work. A good understanding of a problem is real work in its own right.

Problems are never just facts, they are always facts plus frames, evidence plus representation, reality plus politics.

Next time you hear somebody says "the real problem is..." take a step back before jumping to thinking about solutions. Ask your self:

- what type of problem is it?

- who's problem is it?

- what is the evidence for this problem?

- how else might it be represented?

What frameworks and mental models do you use when you think about problems?

What shortfalls do you see with the frameworks above?

And how would you improve them?

Author | Dr Terry Hudsen

Dr Terry Hudsen is a UK-based General Practitioner with a portfolio career that spans clinical practice, system leadership and cross-sector collaboration.

In addition to his clinical work, Terry previously served as Chairman of NHS Sheffield Clinical Commissioning Group (CCG), leading strategic commissioning and system redesign, as well as leading the complex organisational change and transition to Integrated Care Boards. During this he led the establishment of joint commissioning arrangements between the NHS and local authorities and played a part in shaping national policy on maintaining joint health and care commissioning arrangements for local decision-making in place-based health and care systems.

Following the dissolution of CCGs in 2022, he became lead for Population Health and System Development in South Yorkshire’s Integrated Care System, before leaving the NHS to establish an independent consultancy supporting NHS providers, local authorities and VCSE organisations with their capabilities for developing collaborative leadership, strategy and tackling wicked problems.

In 2023, he became Independent Chair of the Bradford Safeguarding Adults Board, where he leads a statutory partnership which comprises partners from health, social care, local government, police, and the voluntary, community and social enterprise (VCSE) sector, focussing on preventing and responding to harm, neglect and exploitation of vulnerable adults.

Alongside these roles, Terry is Clinical Lead for Primary Care and Neighbourhood Engagement and Support within NHS England’s mental health portfolio in the North East and Yorkshire, helping to drive transformation and strengthen collaboration between providers of health and care at local level.

In addition to his medical qualifications from the University of Sheffield, Terry is a proud alumnus of The Open University Business School, where he earned an MBA with distinction in Leadership Practice. He is a Chartered Manager and a Fellow of the Chartered Management Institute. He is particularly interested in leadership across organisational boundaries, with his MBA dissertation focussing on collaboration between the NHS and VCSE sector.

In all his roles he emphasises the power of partnership, culture and shared learning in creating sustainable change. Passionate about building a culture of curiosity and shared purpose across public services, he writes and speaks about adaptive leadership, collaboration and innovation in complex systems. His work aims to inspire leaders and practitioners to think differently, work collectively, and create meaningful impact in the communities they work.

Article previously published on LinkedIn and Wicked Problems Hub.

December 2025

Would you like to contribute an article towards our Professional Knowledge Bank? Find out more.