Neurodivergence in Work: Developing a Culture of Disclosure

Disability Disclosure; To Tell or not to Tell?

Considering whether to disclose a hidden disability or not is a highly personal decision, and one which can be quite complex to navigate.

But what exactly is disclosure, why does it matter, and what are the implications of an employee disclosing their hidden disability at work? This article aims to address these questions, discuss the benefits of disclosure, and better understand how managers can develop a culture of disclosure within their organisation.

What is Disclosure?

Disclosure is defined as “the act of making something known” (Cambridge Dictionary, 2021). In relation to disability, this specifically relates to a person communicating details of their disability to another, and within the further context of employment, an employee sharing information with a colleague, typically someone in a higher position of authority.

The decision to disclose is entirely personal, providing an opportunity to request accommodations but carrying a risk of discrimination. Although both direct and indirect discrimination is covered by the Equality Act 2010 (Gov.uk, 2015), this can be difficult to prove, as “the employer may mistreat the employee under a different pretext” (Booth, 2016, p105). Disclosure at work may also bring a label of being ‘different’ or ‘othered’, putting the individual at risk of being socially and/or professionally excluded. Similarly, someone who feels unable to disclose may struggle without accommodations and be seen as ‘different’ regardless.

Austin, an autistic civil servant, articulates the difficulty of this decision in Booth (2016, p36).

I was ashamed of this condition. I never used to tell anybody. People would see it as a weakness and take advantage or would treat you as a freak or discriminate against you. I thought I was in danger of deterring people.

While there is no legal requirement to disclose, legal protections cannot be accessed without doing so.

Why Disclose?

Generally, the act of disclosing a disability to an employer, other than at the point of entry to role, is initiated in either one of two situations:

- Things are going well, and the employee uses it as an opportunity to diminish negative perceptions of their condition, or,

- Things are not going well, and the employee wishes to open a dialogue of what might help them perform better (Simone, 2010, p119).

Understanding the rationale for disclosure provides the manager with a frame of reference for that person’s behaviour. Discussions regarding potential accommodations in respect of this information can be initiated in response.

Nevertheless, there are alternatives to disclosure. Divulging sensitive medical information should not be the only way for an employee to optimise their working environment. The employee may choose to ask for accommodations such as an exemption from hot-desking, the use of text-to-speech software, or home working considerations. Yet, these are more likely to be approved if the employer has a legal duty to consider these adjustments by way of disability legislation.

Benefits of Disclosure for the Employee

As highlighted earlier, the act of disclosing can be a challenging decision for any employee to make. However, it does offer some protection in law. It also presents an opportunity for the employee to describe the strengths attributed as part of their condition and explain how these relate to role. For example:

because of my autism I am highly attentive to detail and spot mistakes easily, providing me with a quiet workspace helps me do this better.

Framing the disability positively diverts focus towards what the person can do, rather than a narrow concentration on their difficulties.

Marvopoulou and Sideridis (2014) conducted research which revealed that knowledge and attitudes are improved when neurotypical (i.e., non-autistic) children have contact with known autistic peers. By disclosing a disability, the employee is better positioned to positively influence colleagues about their condition and improve attitudes more generally. Although, it should not be incumbent on the disabled person to do so.

Benefits of Disclosure for the Employer

Employing a richly diverse team brings deeper and wider insights into work practices, more accurately representing the communities served by the organisation. When people are given the tools to help them work at their best, they perform better, becoming more engaged and productive at work in response.

In the UK, roughly one in five people are disabled, with 80% of this figure having a hidden disability, such as ADHD, dyslexia, or Tourette’s syndrome (HiddenDisabilities.com, 2021). Employees, if not disabled themselves, are likely to have a personal connection with disability. It is reasonable to suggest that being known as a disability friendly employer may improve the reputation of the organisation and attract higher numbers of disabled applicants.

Employees have a diverse range of needs which the employer has a responsibility to consider. The risk of disability discrimination proceedings can be mitigated by operating in a legally compliant manner (Scheiner & Bogden, 2017, p36). Furthermore, supporting these needs can help employees stay in work longer, lowering recruitment and training costs. The employee no longer becoming trapped in a cycle of hire and fire when lack of understanding causes the relationship to break down.

Developing Conditions to Encourage Disclosure.

Employees will only feel empowered to disclose if they trust that their organisation will listen to them and treat them fairly, or if left with little choice in fear of losing their job Scheiner & Bogden, 2017, p39). Ideally, employees will choose to disclose for positive reasons, rather than as a protective response.

Employees may choose to disclose and not be able to articulate or advocate for their needs. Should this occur, providing a non-judgemental space to openly discuss strengths and challenges can help create meaningful dialogue, and allow accommodations to be tested free from bias.

Scheiner & Bogden (2017, p39-40) suggest a five-fold approach to create favourable conditions for disclosure.

- Workplace training, delivered by disabled trainers, can increase awareness and understanding of different lived experiences. Gillespie-Lynch et al (2015) discovered that training about autism, which included discussions of neurodivergence, decreased stigma and enhanced knowledge of autism.

- Recruitment practices which support neurodivergent applicants can encourage applications from a wider range of jobseekers. These could be measures such as advance sight of interview questions, interviewer profiles, layout and accessibility information, and clear interview expectations.

- Employee networks can raise awareness, enable the sharing of best practice, and provide another avenue of peer support in work. Diversity practices are thereby driven from all areas of the organisation.

- Clear information on how to request accommodations and who to request to can remove hidden communication barriers and create more avenues for disclosure.

- In-work mentoring programmes can pair experienced and new team members together to form a ‘buddy system’. Neurodivergent mentors and mentees can support each other in navigating the hidden norms and culture of the workplace. A thorough induction can also clarify expectations around ‘the way things are done here’. Having an ally in work removes some uncertainty and provides another support mechanism in retaining employment.

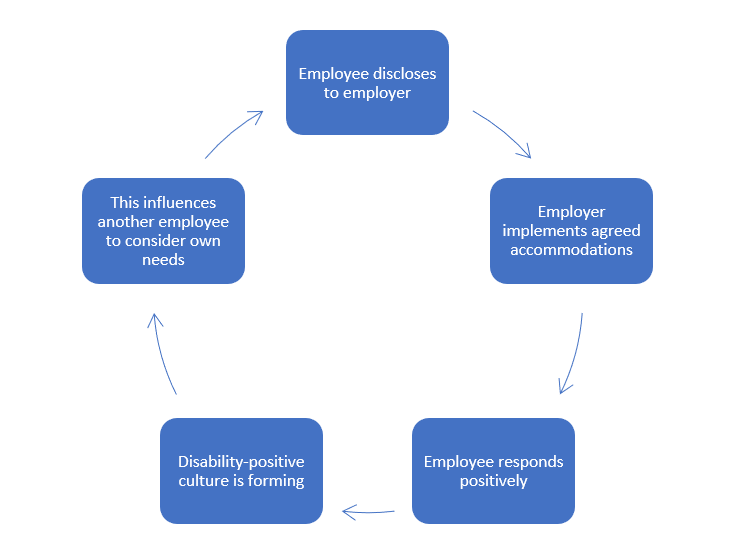

Managing career progression well is key to ensuring disabled staff have clear routes to leadership. The ability to identify disabled leaders in prominent roles can help others be open about their own experiences of disability. This perpetuates a virtuous cycle where each positive interaction feeds upon itself to continuously improve the next.

Virtuous cycle of disclosure:

Perhaps the simplest way to bring about positive culture change is just to ask, “what do you need from us for you to get the most value from your role”?

The Government recently announced a new autism strategy for 2021-2, strengthening their commitment to support more autistic jobseekers into employment (Gov.uk. 2021a). A new 2021 disability strategy supports this, aiming to improve outcomes for people with disabilities over the long and short-term (Gov.uk, 2021b).

Disabled representation matters, yet voices can only be heard if people are willing to listen. Michael Bloomberg, a former Mayor of New York, urges

progress is not inevitable, it’s up to us to create it.

To Conclude

The issue of disclosure is a very individual decision to make. However, organisations can make this easier by developing a culture where strengths and challenges are openly discussed. The suggestions in this article are theorised to deliver a tangible benefit to both organisation and the employee. In turn, these changes are felt to contribute to a virtuous cycle of improvement, enhancing work conditions and initiating change more aligned with the 2021 UK government strategy on disability.

© Tracy Smith, 2021

About the Author

Tracy Smith graduated from The Open University in 2020, achieving a first-class honours degree in Business Management. Since graduation, Tracy has been employed as a mentor for a non-profit organisation, supporting autistic adults to explore, develop, progress, and achieve highly personalised career goals. More recently, Tracy has begun working with organisations to design more inclusive practices and increase the diversity of their teams.

Tracy Smith graduated from The Open University in 2020, achieving a first-class honours degree in Business Management. Since graduation, Tracy has been employed as a mentor for a non-profit organisation, supporting autistic adults to explore, develop, progress, and achieve highly personalised career goals. More recently, Tracy has begun working with organisations to design more inclusive practices and increase the diversity of their teams.

Tracy believes that everyone benefits when organisations create conditions where people can utilise what they need to flourish. Alongside her work on diversity, equity, and inclusion, Tracy is returning to The Open University to study towards an MEd in Leadership and Management, commencing October 2021.

References

- Booth, J (2016). Autism Equality in the Workplace. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers. p36

- ibid, p105.

- Cambridge Dictionary. (2021). Disclosure. Last accessed 28 August 2021.

- Gillespie-Lynch, K., Brooks, P.J., Someki, F. (2015). Changing College Students’ Conceptions of Autism: An Online Training to Increase Knowledge and Decrease Stigma. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders 45(8). p2553–2566.

- Gov.uk. (2021a). Autism strategy implementation plan: 2021 to 2022. Last accessed 28 August 2021.

- Gov.uk. (2015). Equality Act 2010: guidance. Last accessed 28 August 2021.

- Gov.uk. (2021b). National Disability Strategy: Forewords, about this strategy, action across the UK, executive summary, acknowledgements. Last accessed 28 August 2021.

- Hiddendisabilities.com. (2021). What is a Hidden Disability?. Last accessed 29 August 2021.

- Mavropoulou, S. & Sideridis, G.D. (2014). Knowledge of Autism and Attitudes of Children Towards Their Partially Integrated Peers with Autism Spectrum Disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders 44(8). p1867–1885.

- Scheiner, M., Bogden, J. (2017). An Employers Guide to Managing Professionals on the Autism Spectrum. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers. p36.

- ibid, p39.

- Simone, R (2010). Aspergers on the Job. Texas: Future Horizons Inc. p119.

Would you like to contribute an article towards our Professional Knowledge Bank? Find out more.