Motivating Staff: Adapting the Corporate Approach to the Public Sector

About the Author

Carlo E. Stasi, MBA

Carlo is a corporate communication expert with a 18-year track record creating and implementing campaigns that extend brand and organisation vision. Carlo has sound experience both in the private sector and in supporting European Commission's awareness raising initiatives.

In this article Carlo examines ways of motivating staff with limited available rewards and targets, and within a public sector culture.

Table of Contents

1. From Private to Public

1.1 Welcome to bureaucracy

1.2 “Be motivated please!”

1.3 Corporate vs. public in three models

2. A 6-piece toolkit

2.1 Don’t rush: It takes time

2.2 Making your arrival an event

2.3 The link between job description and reality

2.4 Integrating - then communicating - goals

2.5 Intrinsic rewards matter

2.6 The Information Loop: Be generous

3. References

1. From Private to Public

1.1 Welcome to bureaucracy

For a corporate manager, landing in the public sector will likely represent a culture shock. Public bodies are shaped as bureaucracies, whose main feature generally consists in clearly defined roles and relationships. Ideally, bureaucratic structures are rationally organised to achieve specific and measurable goals, and in principle offer many advantages compared with other organisational forms (Weber, 1947). However, bureaucracies also often are associated with inefficient public administrations.

Not surprisingly, most of the structural problems in such organisations originate from weaknesses in managerial practices (Child, 1984). It is likely that managers rooted in the private sector need to adapt their people management style – and their approach to staff’s motivation in particular - to the new reality of the bureaucratic structure.

1.2 “Be motivated please!”

Fostering motivation is a core aspect of people management. Inarguably, motivated staff can make the difference in terms of productivity, as they put a great deal of discretionary effort into their daily tasks. Due to a number of constraints typical of bureaucratic organisations (rigidly codified roles and career paths, formal and informal red tape that may hamper organisational innovation, poor definition of performance standards, unethical behaviours as a consequence of job security, and so forth), influencing people’s motivation may pose extra challenges to newly appointed managers with a professional history in the corporate world.

‘Motivating people’ as such can seem as feasible as forcing your lawn to grow. On the other hand, just as with your lawn, you can create the conditions for motivation and high performance. Becoming aware of your own assumptions about what motivates and demotivates people – and people in your team - is indeed a good start. The next step in your quest to motivate each individual is to put your assumptions to the test and eliminate those that are flawed.

1.3 Corporate vs. public in three models

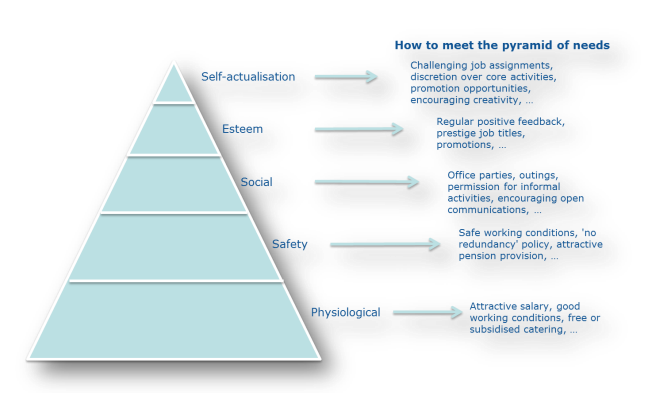

The differences between the corporate environment and a public administration can be analysed through a widely used motivation model, the Maslow pyramid (1954), which identifies five categories of needs (physiological, safety, social, esteem, and ‘self-actualisation’). These categories are hierarchically ranked: once the ‘bottom-of-pyramid’ needs are satisfied, people start looking at the higher-order set of needs.

In this view, management must ensure that the appropriate set of needs are met in accordance with the professional and psychological development of each individual. Organisations have developed a wide range of prescriptions based on Maslow’s hierarchy of needs (Huczynski and Buchanan, 1991):

Diagram 1 – Maslow’s hierarchy of needs and simple prescriptions

There is good news and bad news.

The good news: public administrations usually perform well in the first three levels of the pyramid – which is not always the case with most small and medium-sized organisations. In most public administrations, factors such as working conditions, pension provisions, safety, ‘no redundancy’ policies as well as permission for informal activities, outings, office parties, etc. are generally well established, thoroughly codified, and in many cases at the core of the human resource department’s duties.

The bad news: for most people, those sets of needs are barely enough to avoid dissatisfaction (“hygiene factors”), but not sufficient to create satisfaction (Hertzberg et al., 1959):

Diagram 2 – Herzberg’s view of motivation

Therefore one might argue that with such good foundations in terms of Maslow pyramid, public administration managers spend a lot of time and effort to influence their people’s motivation by working on the higher-order sets of needs, on motivation factors. Sadly enough, this is quite a rare occurrence. This is where formerly corporate managers, now freed from the burden of juggling the five set of needs at once, can contribute the best of their experience.

2. A 6-piece toolkit

2.1 Don’t rush: It takes time

Once settled into your new assignment as a public administration manager, resist the temptation to adopt ‘one-size-fits-all’ solutions for improving motivation in your team. Even more important, refrain from simply re-using what worked in the corporate world: ‘motivation’ and ‘hygiene’ factors may turn out to be significantly different here. The short prescription: do not miss any opportunities to talk with your people and to question your assumptions.

Careful, though: first you need to win your people’s trust by establishing a climate of open communication. This means focusing on problem-solving rather than assigning blame; if you ever express criticism, make it clear that the aim is to help and improve; recognise that misjudgements and errors are inevitable; praise any contributions, irrespective of role or hierarchical status; always provide feedback. This may cost you time and energy, but it is well worth the investment: people respond positively to genuine attention by their management and are keen to discuss what increases their motivation, but only after open communication has been established.

2.2 Making your arrival an event

Besides the employment contract, usually written and legally binding, and the informal operational agreements (made explicit, for instance, in detailed discussions about tasks) there is always a psychological contract which includes any employee’s expectations from the organisation, as well as his understanding – and most often assumptions – about what management expects from him.

Trouble is, the psychological contract is in most cases tacit, unwritten, unacknowledged, and taken for granted. Each person creates his/her own psychological contract at the start of the working relationship - sometimes even before the relationship starts; the contract changes as a consequence of changes in the organisation, the external environment, and individuals’ personal priorities.

Public sector is no exception to this. It is therefore crucial that the newly-appointed manager does not miss the opportunity to make the psychological contract explicit through carefully prepared one-to-one conversations, and re-formulates it with a view to matching expectations – for both manager and employee. After all, managers, too, have their own psychological contract.

2.3 The link between job description and reality

Clear job descriptions for each role, together with well-defined reporting lines, are core to bureaucratic structures. Therefore, public administrations are strong in job definition and immune from ambiguities. However, as in the corporate world, you might find your people’s job descriptions obsolete, dating back to the last time a manager codified staffs’ roles and tasks. Then the context changed and the job descriptions quietly drifted away from reality. As a consequence, staff are unsure about what is expected from them, and gather evidence of managerial inconsistency. Obviously, such situations do not increase motivation.

Do not miss the opportunity to re-formulate your people’s job descriptions taking into consideration the individual expectations – which you should now know, after discussing their psychological contract. You should endeavour to align the tasks with the development of the individual employee’s skills and responsibilities, and their continuing development in accordance with desires and expectations. This will generate the satisfaction of performing meaningful work (Hackman and Oldham, 1980) and should be the starting point for team re-organisation and activity planning.

2.4 Integrating - then communicating - goals

Integration of goals is of the essence (Armstrong and Baron, 1998): individual goals must be consistent with team goals, department’s, senior management’s, and the goals of the public administration as a whole. In doing so, be sure to give your staff SMART goals: specific, measurable, agreed, realistic, and time-bound.

Once you have outlined your integrated chain of goals, do not forget that every member of your team needs to understand what is asked of everyone. There is indeed some communication to carry out after goals have been agreed.

2.5 Intrinsic rewards matter

In public administrations, where career progression is not always strictly linked to performance and bonuses are quite often symbolic, a sense of achievement for a job well done and satisfaction for improved skills are crucial to people motivation. These ‘intrinsic rewards’ are sparked by the work itself and result from careful management of expectations.

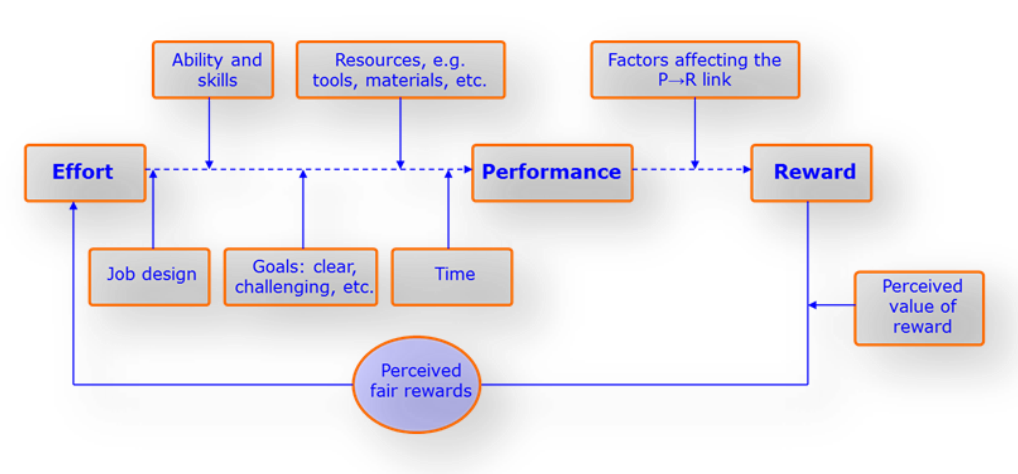

Simply put, people need to be sure that if they make an effort they will achieve the desired performance. Your role as a manager is to link effort and performance. To do so, you may want to use the following checklist: Is the individual able to perform as he/she expects? Are SMART goals there? Are the appropriate resources in place? Are deadlines realistic? Does the person have an updated job description and clear tasks?

Additionally, you must link performance and outcomes (i.e. rewards or costs): ensure that rewards for good performance - or punishments for poor performance - are perceived as fair. If you do not have decision power on all of the rewards (see prescriptions of diagram 1), make people aware of such constraints and do not hesitate to acknowledge superior work. Genuine praise is perhaps the most valuable intrinsic reward.

2.6 The Information Loop: Be generous

Every employee should be clear as to their roles and responsibilities, the pace of activities, principal deadlines, current achievements, lagging activities, if any, and why. Consider sharing a timed workplan accessible to the entire staff, using colour codes – or whatever you find useful – to make tasks, and task owners easily understood. This will help give your team a sense of direction, making your strategy tangible and real to others (Bennis, 1998).

3. References

- References to conceptual frameworks and models as described in B713 Fundamentals of Senior Management (2005), The Open University Business School, Milton Keynes.

- Armstrong, M. and Baron, A. (1998) Performance Management: The new realities, London, IPD.

- Bennis, W. (1998) On Becoming a Leader, Reading, Arrow.

- Child, J. (1984) Organisations: A guide to problems and practice, London, Harper & Row.

- Hackman, J.R. and Oldham, G.R. (1980) Work Redesign, Reading, Mass., Addison-Wesley.

- Herzberg, F., Mausner, B. and Snydeman, B.B. (1959) The Motivation to Work, New York, Wiley.

- Huczynski, A. and Buchanan, D. (1991) Organisational Behaviour, London, Prentice-Hall.

- Maslow, A.H. (1954) Motivation and Personality, New York, Harper & Row.

- Weber, M. (1947) The Theory of Social and Economic Organisations, New York, Oxford University Press.

©Carlo E. Stasi, 2013

Reviewed 2022

Would you like to contribute an article towards our Professional Knowledge Bank? Find out more.