When words get in the way: Why common language matters in collaboration

Cross-sector collaborations and alliances are increasingly becoming the norm in the public service organisations. In my sphere of work, over recent years, we have seen the introduction of Integrated Care Partnerships, Primary Care Networks, Provider Collaboratives, Health and Care Partnerships, VCSE Alliances and Safeguarding Partnerships, to name a few.

More recently, policy from the 10 year plan has opened up the path to Neighbourhood Health Services - bringing together teams from multiple health, care and community organisations to improve outcomes and address inequalities in outcomes from and experience of care?

Most of these partnerships start with energy and optimism - with the hope that by working together we will be able to make a bigger difference than we can alone. However, if you've spent any time in partnerships, you'll know that there is sometimes another side to this story: misunderstandings between partners, and a sense of frustration at seemingly slow progress.

There are many factors that contribute to this, including poor communication as a result of the lack of a common language.

As with my previous articles, I want to reflect on what the management science and literature has to say about the language of collaboration and what we might be able to do about it, drawing on my insights as a dual qualified medical doctor and Chartered Manager.

When Words Get in the Way

All partner organisations, their teams and different sectors within a collaboration, have their own jargon, shorthand, seemingly bizarre acronyms, and assumptions about words. Let's look at an example I've come across several times - the phrase "care plan".

What does it mean to you? And what do you think it might mean to others?

In my world as a GP, a care plan is an agreed course of action with a patient to treat or support them with a particular condition. But, in the mental health world "care plans" often reflect a bureaucratic policy approach (the Care Programme Approach or "CPA"). For a social care professional, it is likely to be a description of the things done on a daily basis to provide personal care to somebody. To a person receiving care, support and treatment it might mean something completely different - and they are arguably the most important people in our collaborations!

To a person receiving care, support and treatment "a care plan" might mean something completely different - and they are arguably the most important people in our collaborations

This list could go on, but my key message here is that something as simple as a "care plan" means something different to different people.

In leadership spheres, this can go further. Not only is there a risk of confusion or misunderstanding of what is being discussed within a partnership, but partners can leave a meeting convinced that they disagree on something, when in reality they have simply been describing the same thing in a different way. Worse still, everyone may have left the meeting in agreement based on apparent terminology where there are fundamental differences which only become apparent much further down the line - often at a crisis point of disagreement or asking 'how did we end up here?’

There is a real danger in this: misunderstandings harden over time. They lead to polarisation. This can turn into mistrust. Once this happens, the energy and optimism of the collaboration starts to wane.

Collaborative Advantage: The Upside and the Drag

The Theory of Collaborative Advantage (Huxham and Vangen, 2005) is one of my favourite theories for the bases of collaboration. It states that partnerships really add value if they deliver outcomes that no single organisation could achieve on its own. However, there is a downside in collaboration - the inertia that results from endless meetings where nothing seems to move forwards at pace.

Sound familiar?

Language and communication is something that often tips the balance between collaborative advantage and collaborative inertia.

(Note: there are many other contributory factors in this theory: it's essential reading - and we'll cover more in future articles!)

Shared language, or common language, can help to build trust and action. Without this, your partnership can easily end up in a rut. Even when things in the partnership are moving forward, it's difficult to ignore that collaboration is full of tensions. Leaders are often given contradictory advice by different leadership gurus: be inclusive, but be decisive... build trust, but protect your organisation's interest... act as one, but hold on to identity...

These contradictions show up in language all the time. Let's consider "integration" - the flagship word of so many health and care policies. It's a positive sounding term that so many of us talk about. But what does it really mean? If you ask five different sectors they will describe it in five different ways. As mentioned before, how would the people receiving services describe integration to you? And how would their perception of "integration" benefit them? Would they describe it the same way as an ops manager, a commissioner, a clinician or a politician?

The term "success" is even up for grabs in collaboration - what do we really mean? It depends on who you ask...

Competing Logics and the Politics of Language

Partnerships don't operate on a neutral ground. Ferlie and Ongaro's (2015) work on public service management and partnerships notes organisations are shaped by competing logics: professional, bureaucratic and political.

Each of these logics brings its own vocabulary and cognitive assumptions. As discussed earlier in this article, it means that different sectors have different ways of describing and understanding things. For example, clinical risk; statutory responsibilities; governance and lived experience, to name just a few of a paradigms. None of these perspectives is wrong, but without some form of translation, the languages can collide.

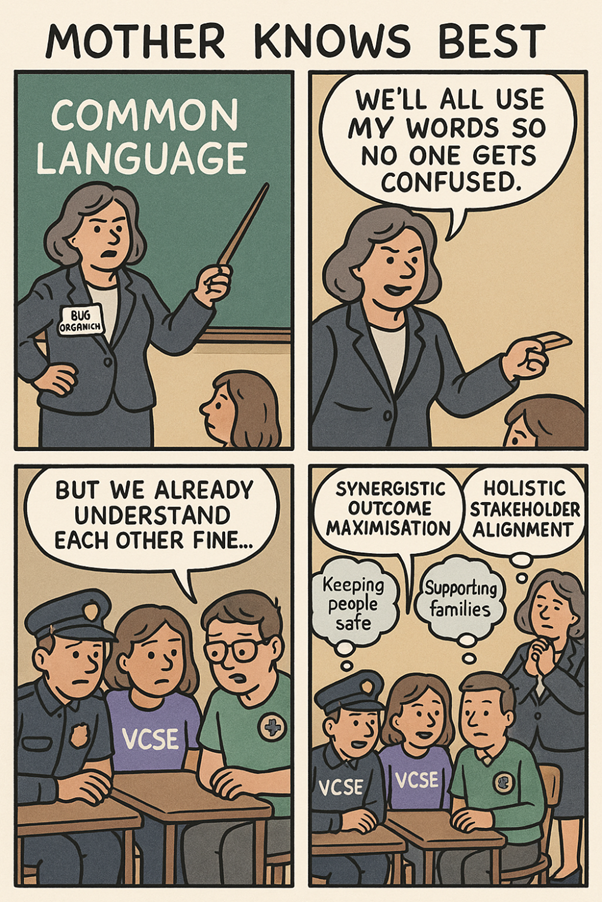

To complicate matters further, we need to consider power dynamics. Larger organisations - often (but not always) huge NHS organisations with their own centre of gravity - tend to set linguistic terms in partnerships. Their jargon often becomes the de facto "common language". This isn't always intended, but it can result smaller organisations and VCSE voices feeling marginalised or not heard in discussions.

Humorous AI image creation: Big organisations often have the power dynamic to affect common language

What might seem like consensus in a partnership meeting might actually be the amplified voice of one partner above another.

Absorptive Capacity: Making Sense Across Boundaries

Collaborations need the ability to use new knowledge together to create value through the work of their partnerships. In the public sector, we operate in a knowledge economy - think about new scientific advances, keeping professionals up to date, learning about better and more efficient ways of making an impact.

Understanding absorptive capacity (ACAP) helps us here.

ACAP describes how organisations use their capabilities to acquire, assimilate, transform and apply new knowledge. Developments on this theory describe "dynamic capabilities" - the ability to adapt and reconfigure in changing conditions.

In partnerships, ACAP must operate at a collective level (rather than just the organisation level). This not just about sharing information between partners, but making sure that knowledge is understood by all partners in the same way, so that decisions can be made and actions taken.

This involves:

- Acquisition: bringing knowledge in from across partners and sectors

- Assimilation: sense making and sense giving so everyone understands the same thing

- Transformation: combining insights from different logics to create new perspectives

- Application: using the shared understanding to make joint decisions and act together

Studies have shown that in public services, ACAP enables not just innovation, but policy adaptation. This isn't just a pie in the sky theory - researchers have developed tools to assess ACAP within partnerships to help identify areas of weakness and strengths.

Further extensions of ACAP demonstrate several antecedents that can help create the conditions for shared language and meaning within partnerships. These include so called socialisation, co-ordination and system capabilities - describing show a collaborative forms a shared ideology and culture, develops formal knowledge exchanges, and develops cross-sectional interfaces, shared learning and participative leadership.

In other words, relationships and formal systems both matter, if partners are not just going to share knowledge but mean the same thing by it.

Pitfalls to Avoid

From the theories discussed above, there are several pitfalls that are apparent for cross-sector collaborations:

- Illusions of common ground: Where shared words might mask divergent meanings

- Polarising misunderstandings: where different terms for similar ideas can create the impression of conflict

- The politics of translation: where dominant partners impose their language (and sometimes processes) which (unintentionally, or otherwise) silences others

- Capacity differentials: where larger organisations have more resources to absorb and adapt, leaving other partners behind

- Ignoring tensions: where people try to ease differences rather than lean into them which breeds frustration

Practical Strategies

Instead of chasing the mythical "single common language", people working in collaboration should focus on practices that build absorptive capacity across all partners:

- Co-create a living dictionary of terms - but make sure it is more than a glossary of terms that everyone is 'expected' to adhere to

- Have safe 'translation' spaces where asking the "silly question" about what something means is encouraged

- Use reflexive dialogue to surface differences in meaning, rather than trying to smooth other the cracks

- Balance vocabulary that values both data metrics and lived experience stories

- Invest in strengthening collective absorptive capacity - socialisation capabilities (e.g. cross sector training, secondments, networking and shadowing), system capabilities (e.g. joint reporting, agreed processes and shared data platforms) and coordination (share learning, joint activities)

- Spend time with colleagues of different disciplines, from different sectors, and different social backgrounds to understand their logics

- As individual leaders, check your own cognitive biases and don't adhere too strongly to the words you've always used to describe things - explore new perspectives.

- Embed lived experience voices and communities in forming the language - after all they are who should be here for!

Final thoughts

Collaboration isn't a "win-win" by default - Huxham and Vangen are clear about this in their theory of collaboration. Collaboration is messy, filled with tensions and it's hard graft!

But... when partners pay attention to language, recognise the competing logics described by Ferlie and Ongaro, and work towards building absorptive capacity, they will give themselves a fighting chance of moving from collaborative inertia to collaborative advantage.

It's not about saying the same words. It's about meaning something together. And then acting on, together!

Author | Dr Terry Hudsen

Dr Terry Hudsen is a UK-based General Practitioner with a portfolio career that spans clinical practice, system leadership and cross-sector collaboration.

In addition to his clinical work, Terry previously served as Chairman of NHS Sheffield Clinical Commissioning Group (CCG), leading strategic commissioning and system redesign, as well as leading the complex organisational change and transition to Integrated Care Boards. During this he led the establishment of joint commissioning arrangements between the NHS and local authorities and played a part in shaping national policy on maintaining joint health and care commissioning arrangements for local decision-making in place-based health and care systems.

Following the dissolution of CCGs in 2022, he became lead for Population Health and System Development in South Yorkshire’s Integrated Care System, before leaving the NHS to establish an independent consultancy supporting NHS providers, local authorities and VCSE organisations with their capabilities for developing collaborative leadership, strategy and tackling wicked problems.

In 2023, he became Independent Chair of the Bradford Safeguarding Adults Board, where he leads a statutory partnership which comprises partners from health, social care, local government, police, and the voluntary, community and social enterprise (VCSE) sector, focussing on preventing and responding to harm, neglect and exploitation of vulnerable adults.

Alongside these roles, Terry is Clinical Lead for Primary Care and Neighbourhood Engagement and Support within NHS England’s mental health portfolio in the North East and Yorkshire, helping to drive transformation and strengthen collaboration between providers of health and care at local level.

In addition to his medical qualifications from the University of Sheffield, Terry is a proud alumnus of The Open University Business School, where he earned an MBA with distinction in Leadership Practice. He is a Chartered Manager and a Fellow of the Chartered Management Institute. He is particularly interested in leadership across organisational boundaries, with his MBA dissertation focussing on collaboration between the NHS and VCSE sector.

In all his roles he emphasises the power of partnership, culture and shared learning in creating sustainable change. Passionate about building a culture of curiosity and shared purpose across public services, he writes and speaks about adaptive leadership, collaboration and innovation in complex systems. His work aims to inspire leaders and practitioners to think differently, work collectively, and create meaningful impact in the communities they work.

Article previously published on LinkedIn and Wicked Problems Hub.

December 2025

Would you like to contribute an article towards our Professional Knowledge Bank? Find out more.