Day 149, Year of #Mygration: Does Diversity Impact Negatively on Social Capital?

Following the publication of my previous blog post, I was gratified to receive so many comments from friends and colleagues. One question that stood out, however, was from a colleague who asked for my thoughts on political scientist Robert Putnam’s assertion, following a large-scale research project involving over 30,000 people, that immigration and diversity impact negatively on trust and social capital.

In the same paper, Putnam argues that "the central challenge for modern, diversifying societies is to create a new, broader sense of ‘we’”. But how might we encourage this redefinition, particularly if, to quote Putnam again, “people living in ethnically diverse settings appear to `hunker down` that is, to pull in like a turtle”?

Even using all my experience as a migrant, scholar and activist, providing an adequate response to this question remains a challenge. Before I try, however, I need to flag that social capital has many dimensions, all of which operate at different levels. One typology (developed by Putnam), is based on the relationships between members, organisations and public agencies; relationships which include bonding, bridging and linking.

Following Putnam, ‘horizontal’ relationships of bonding (with family and close friends) and bridging (with neighbours, colleagues or other community groups) need to be supplemented by ‘vertical’ relationships of linking (with those who have different knowledge and resources, cutting across status and similarity and thereby enabling people to exert influence and reach resources outside their normal circles). The richest people socially, then, are those with relationships that bond, bridge and link.

In an attempt to answer these questions, I’d like to share my experience in developing, sustaining and enhancing my social capital in Milton Keynes over the last four years. An experience which strongly supports the argument that involvement in the voluntary sector can help migrants acquire the social capital which will enable them to become socially rich.Is it, however, possible for everyone to be socially rich? How easy is it for migrants to acquire new bridging and linking social capital to replace that which they left behind? Even if it’s easy to acquire bonding social capital through the joining of home-country associations and linking up with family and friends, how easy is it then to move beyond this and engage in activities that generate linking social capital?

Shortly after moving to Milton Keynes, and thanks to Ben Pollard (formerly with Citizens UK) whom I had met at a conference in London a few years before, I got involved in Citizens:MK. Similarly, it was through the Community Foundation for Ireland that I was introduced to the MK Community Foundation. This, however, was just the beginning.

I soon discovered that in order to be active in Citizens:MK and acquire relational power – a pre-requisite in community organising – I needed to be active in one of its member institutions, too. Joining the Church of Christ the Cornerstone, as well as helping me in building my networks within the church, the community and the voluntary sector, was thus the missing piece of the jigsaw. In effect, it marked the beginning of my acquisition of bridging social capital and laid the foundation for my development of linking social capital.

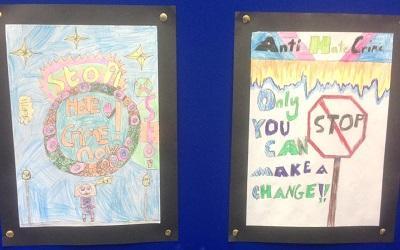

At Cornerstone, in 2016, I worked with colleagues on convening a briefing by Thames Valley Police on hate crimes in Milton Keynes. This event would, over time, lead to the Fight Against Hate campaign which, in turn, would help me to make connections with various institutions including the local council, transport organisations such as Network Rail and Arriva Bus, and the Milton Keynes branch of Thames Valley Police. In a nutshell, civic engagement certainly helped my acquisition of both bridging and linking social capital.

But, to return to Putnam, do I believe that diversity negatively affects social capital? The argument might, perhaps, be valid if migrants engaged only in activities that generate bonding social capital. Although personally I believe – following an argument first put forward by Robert Furbey et al. – that, as it’s frequently the foundation from which they can begin the more difficult project of relating to people unlike themselves, even this should not be dismissed.

Furthermore, while I may invest my activism in organisations and activities that generate linking and bridging social capital, I fully understand migrants who prefer to invest in social practices that generate bonding social capital. There are many reasons why this happens, but we do not need to look too far beyond the response to diversity from some established communities, policy makers and opinion formers to discover an important one.

We also need to distinguish between ethnic social capital (acquired from ethnic associations) and cross-cultural social capital (acquired from mixed and more mainstream organisations), as sociologist Jacobs argues. While too much of the former may impact negatively on social capital in the country of destination, the same may not be true for the latter.

Immigration has certainly not, at a personal level, led to inertia in my civic engagements. My activism has not only helped me to gain social capital, it has also helped me to develop and enhance my intercultural competences – important qualities in the promotion of integration, equality, diversity and social cohesion.

My activism has not only helped me to gain social capital, it has also helped me to develop and enhance my intercultural competences

Immigration may well challenge societies, but civic engagement undoubtedly helps in moving towards a new ‘we’, one embodied in diverse and yet cohesive societies. Through my engagement in cross-cultural social practices I have engaged in campaigns aimed at changing the narrative on diversity and, by implication, identity. I have also been fortunate in receiving positive responses from other actors in civil society as well as from businesses and public institutions. Negative responses may well have led to different outcomes.

Although local, regional and national governments, businesses, civil society and communities all have a part to play, no one need wait until the environment is ‘right’ before they engage in civic activities. Individuals, including migrants, have their own part to play, too. It is, after all, in everyone’s interest to help form tolerant and cohesive societies.

Photo courtesy of pupils at Tickford School in Newport Pagnell, part of MK's Fight Against Hate Campaign

Dr Fidèle Mutwarasibo is a Visiting Research Fellow in The Centre for Voluntary Sector Leadership at The Open University Business School.

This article was originally published on The OU Research website as part of The Year of #Mygration project. Click to read the original article.

Upcoming Events

Doing Academia Differently: Professional Development Symposium for Doctoral Students and Early-Career Academics

Tuesday, March 10, 2026 - 09:00 to 17:00

Michael Young Building, The Open University, Walton Hall, Milton Keynes, MK7 6BB

This one-day symposium on ‘Doing Academia Differently’ will provide inspiration and support for PhD and early-career academics to approach the complex tensions and dilemmas of contemporary academia in new and creative ways.

International Women’s Day: Supporting diverse new motherhoods for work inclusion

Thursday, March 12, 2026 - 11:00 to 12:30

Online Webinar - link below

This webinar from our GOP research cluster will discuss findings from research into how motherhood impacts employment for ethnic minority women.